Brilliant Pebbles All Over Again: The Race to Weaponize Space

On January 27, 2025, President Donald Trump decided to make what was once old new again.

On January 27, 2025, President Donald Trump decided to make what was once old new again. He signed the “Iron Dome for America,” which dusted off the dormant, but never quite bureaucratically dead proposal to develop and deploy (among many other things) “proliferated space-based interceptors capable of boost-phase intercept.”

The project was Ronald Reagan’s idea and part of the reason for his 1983 embrace of missile defense to obviate the need for large numbers of nuclear weapons. Reagan soured on the idea of nuclear war and believed that a shift in mindset from offense to defense could catalyze agreement with Moscow on arms reductions, if not outright elimination. As is almost always the case, the world’s most powerful man—the American president—had to contend with a fractured bureaucracy, commitment to the status quo, and the need for robust offensive arms to ensure that the Soviet military could be defeated in Europe.

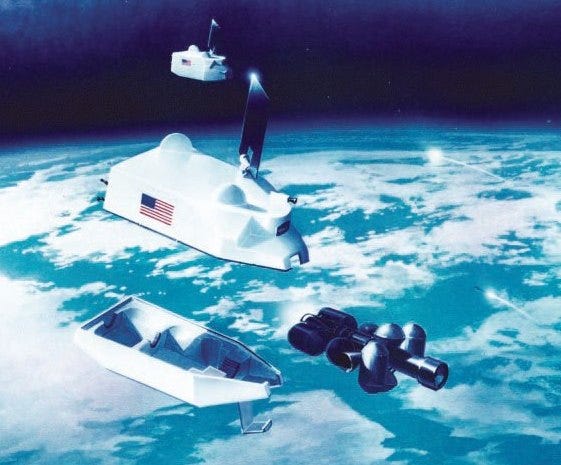

The Strategic Defense Initiative, or SDI, was the organizing program for Reagan’s effort and spawned American investment in many of the hit-to-kill missile interceptors that the United States and allies now use around the globe. Reagan had more grandiose ambitions. He wanted to develop space-based interceptors, initially dubbed “battle stations” before the name shifted to “smart rocks” and eventually “brilliant pebbles.” The idea, in the 1980s and again four decades later, was to house lightweight missiles on hundreds of orbiting platforms, or a brilliant pebble in orbit. A platform would be located over enemy territory, or widely proliferated, so that the United States would have options to strike a missile as it was ascending from earth before it could release its warheads (and presumably decoys) in what is dubbed mid-course flight and before those warheads then decelerated and re-entered the atmosphere to strike targets back on earth.

The space weapons would be used for the first phase, a different set of missiles would be used for the mid-course phase, and a final set of interceptors could be used to attack whatever made it through. If this sounds like a lot, it is. The costs of missile defense have always been the major impediment. The “brilliant pebble” concept required thousands of interceptors according to a 2004 American Physical Society report. The cost of vertical lift, the authors noted in the same report, would make such a system impractical.

The cost of vertical lift has decreased dramatically since 2004 and, with the promise of SpaceX’s Starship, could decrease even more. The idea of large constellations of satellites, once relegated to the realm of science fiction when Reagan first endorsed this idea, is now a reality. The Starlink constellation is a good comparison when thinking about what a space-based missile architecture would look like. The private sector has made tremendous strides to making Reagan—and now Trump’s—missile defense plans potentially feasible. The costs, however, will remain considerable and, as Reagan had to deal with, the promise of space-based missile defense raises sticky alliance-management issues that the Trump administration will have to consider.

A High, but Declining Cost

The cost of space-based missile defense is still very expensive, and the long-term value of this constellation is still up for debate. Money is finite and every decision to spend dollars on weapons for defense translates into less money to spend on weapons for offense. The question, then, is where to make defense investments: offense or defense? I have always believed in offense, but others disagree. As Todd Harrison at the American Enterprise Institute has written, even with the dramatic decrease in launch costs with SpaceX, “the total cost to develop, build, and launch an initial constellation of 1,900 space-based interceptors would likely be on the order of $11 to $27 billion.” A system sized to approximately 2,000 interceptors in orbit would help protect the United States from a small, limited attack. The issue with space-based missile defense has always been that the best way to defeat defense is to build more missiles, thereby dramatically increasing the cost requirement of the defender. This is what analysts refer to as the “cost exchange ratio.” Advocates of missile defense have never quite been able to show how the cost of strategic defense, especially when compared to offense, makes economic sense.

There is also another way to complicate a boost-phase missile defense: decrease the “burn time” of the offensive missile. In plain English, a missile designer could decrease the time an offensive missile needs to accelerate its payload to the speed required to strike the United States. The less burn time, the less time the United States has to see the missile and strike it before it enters into that middle period where the payload can separate from the rocket body (with decoys). The other issue is that not every nuclear delivery vehicle leaves the atmosphere.

Thinking About Alliances

Alliance management will be something that the Trump administration will have to consider. During the 1980s, European leaders worried that a focus on strategic defense would make them more vulnerable to Soviet short-range attacks and that Moscow’s obvious counter to SDI (building more missiles) would embolden the nuclear abolition movement and undermine NATO cohesion. They also worried about more parochial issues, such as solidifying the United States as the dominant space power. France, in particular, argued that Europe should seek to close the technology gap with America (François Mitterrand was particularly enamored with Silicon Valley) to develop a pan-European alternative to US satellites and launch capabilities. The other part of this was the embrace of the dual-track approach, which was a pan-NATO agreement to deploy US-operated nuclear missiles (Pershing II and Gryphon) in Europe to counter Moscow’s deployment of the SS-20.

The finalization of the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) eliminated this class of delivery vehicles, directly addressing these European concerns. The United States withdrew from the INF Treaty during Trump’s first term, mostly because Russia was cheating. China also had developed the world’s largest arsenal of medium range missiles and was never subject to the INF Treaty’s restrictions. In response, the United States developed Typhon, which can carry both the Tomahawk and SM-6 missiles on ground-based launchers, and deployed them in both Europe and Asia. The missile race is on. All of this raises questions about how to make future military investments.

For now, the Trump administration wants it all—and deployed missiles all around the world. In addition to the space-based component, the executive order calls for the “deployment of underlayer and terminal-phase intercept capabilities postured to defeat a countervalue attack.” Countervalue is a fancy term for a population center, or city, and countervalue targeting is when you hold cities at risk with nuclear weapons. Trump’s Executive Order is asking for missile defense sites around the United States. In many ways, this is a throwback to an even earlier era in US air and missile defense, which had Nike missile launchers deployed around the country. I lived beneath one such site and would run by it.

Looking ahead, the promise of this new era of space-based missile defense rests heavily on the technological innovation of SpaceX and, perhaps, Blue Origin. Both of these companies are owned by US billionaires. In the case of SpaceX, Elon Musk’s forays into governance and politics has made him persona non-grata for many European political parties. It also has raised uncomfortable questions about being so reliant on a single person to access space, or in this case, the launch of the interceptors that would be counted on to defend large parts of the globe from nuclear attack.

Mutual defense ultimately relies on trust. Trump has his own unique approach to collective defense, and his flirtation with withdrawing from NATO or extorting South Korea over US basing access could make allies skeptical of this proposal. This skepticism was present in the 1980s, so it is not entirely unprecedented, but the change in American foreign policy is certain to heighten anxiety.

However, we have all seen how this movie ends: France fails to galvanize a pan-European response, Germany remains paralyzed with indecision (before ultimately agreeing to the United States proposal), and the United Kingdom seeks to maintain its place in the special relationship, albeit with reluctance. I assume this is how this will go this time, too, at least amongst US and NATO allies. Asia is different. It is more prepared for the looming missile race, with South Korea and Japan both pushing ahead with their unique approaches to missiles and missile defense.

Russia, China, and North Korea are also certain to respond to any advance in US space-based missile defense. The best way to do this is to build more missiles. Russia will soon be free to do so once the New Start Treaty, which limits both warheads and delivery vehicles deployed, expires in February 2026. China is at the start of a massive buildup of its nuclear forces. North Korea can and will build more nuclear weapons. The world is amidst a major arms buildup. The best option would, of course, be to try and slow it down. This was the basis for US-Soviet detente in 1969, which was heralded as the end of the Cold War.

The Coming Arms Race

However, I am not naive. The arms race is certain to accelerate in the near future and it will suck up billions of defense dollars in the process in programs that may never come to fruition. The economics of space-based missile defense have changed, but the physics of detection and interception have not. Therefore, even with the decrease in launch costs, the investments required remain considerable. The cost will be even higher if Trump pursues “countervalue” defenses around American cities. It will force tradeoffs in the development of future US weapons and platforms (including Typhon) and be rife to attack in a toxic political environment. Europe would be wise to develop its own Typhon variant, using existing cruise missile models for an alternative to the United States. This could increase European leverage, prepare the continent for expected US troop withdrawals to support the president’s Indo-Pacific ambitions, and could shelter NATO countries from accusations that they do not do enough to burden share.

The post-Cold War world that so many have gotten used to is over. The United States and Europe made conscious decisions to disarm. Russia did so too, albeit because the country was mired in economic collapse. China made no such decision. The restraints that limited Russian and Chinese arms buildup have loosened considerably. The United States and Europe are taking immediate steps to bolster capabilities: The promise of missile defense in space is a good example. However, for all of the promises of this system and the very real developments that could enable its development, the risks of an uncontrolled arms race are the same as they were during the Cold War. Buckle up.

Aaron Stein is the President of the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

Very clear and compelling, thank you Aaron!